Last year, the Stop Torture Impunity campaign persuaded the Government to cease its efforts to protect British soldiers from prosecution for war crimes after five years. Seth Farsides spoke to Tracy Doig of Freedom from Torture about the collaboration and how the Government was persuaded to change tack on such totemic policy.

Freedom from Torture’s Finsbury Park office in London characterises the campaign I was there to talk about: caring, considerate, and with meticulous attention to detail.

‘It was specifically designed with survivors in mind’ Tracy Doig Head of International Advocacy and Accountability tells me as we make our way up to the third floor. ‘Notice how all the corridors are curved? That’s intentional, so that it doesn’t prompt memories of detention centres, or have that institutional feel.’

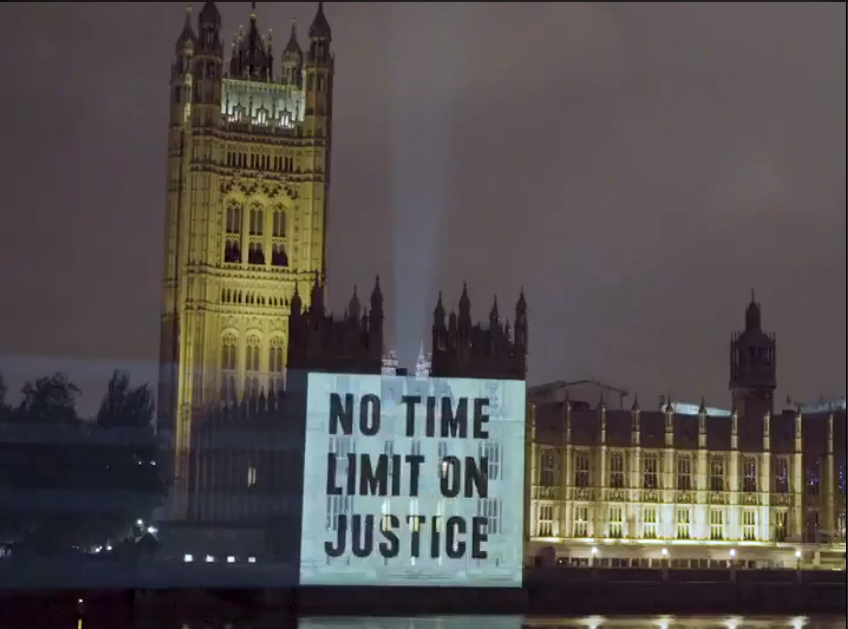

Freedom from Torture, alongside survivor-led network Survivors Speak OUT, was this year’s winner of the Sheila McKechnie Foundation’s Campaign of the Year Award. They coordinated a campaign to remove torture, war crimes, and crimes against humanity from the impunity provided by the Overseas Operations Bill. The legislation, with its ‘presumption against prosecution’, would have protected British armed forces personnel from allegations of acts of torture and other war crimes committed abroad more than five years earlier.

Key things I learned:

- Coalition working was key, don’t overlook unusual allies

- Be laser focused on your aims – even if it means hard decisions

- Make the most out of the cards you’ve been dealt

- Think about who should deliver each message, and time them well

- These things can take a toll, make sure you check in with each other

‘We worked in coalition right from the beginning,’ Tracy told me as I sat down next to a mannequin dressed as a border patrol guard, arresting Paddington’s Aunt Lucy. ‘An initial core group of organisations – Amnesty International, Reprieve, Liberty, REDRESS, Human Rights Watch, Rights and Security International (RSI), Centre for Military Justice, and the Quakers– met regularly to strategise, co-ordinate, and plan messaging. It was useful but, from there, we lurched from crisis to crisis.’

It’s an honest opener. The legislation central to this campaign was working its way through Parliament right as the pandemic hit, pressing pause not just on the legislative agenda but the world at large. While coalition working, which is something we at SMK know that campaigners would love to do more of, can become costly or a logistical nightmare. It seemed like as good a place to start.

SF: In terms of the collaboration, what was it like working with a big group? How did you coordinate between individual aims and shared outcomes?

TD: We took difficult strategy decisions early. It was agreed that, for most organisations in the coalition, the focus would be on part one of the Bill, which was around the presumption against persecution. Two organisations chose to focus on part two of the Bill, which was the Centre for Military Justice and RSI.

I think that strategic decision very early on, to focus on part one, despite all being equally concerned about part two, helped the win. But it could be said that we sacrificed the win on part two.

The other early strategic decision, made collectively, was focusing on torture. That was because the inclusion of torture in the legislation was something so very clearly wrong and undermined the Government’s narrative: ‘If you oppose this bill, you oppose our brave men and women that protect us.’

It was an incredibly tight knit group that met regularly and grew as the Bill progressed. The addition of two All-Party Parliamentary Groups, on Drones and the Rule of Law, became very influential, as they brought with them academics and international law experts. We ended up with a very broad coalition that included people who were very effective in critiquing the Government’s responses and drafting amendments for the House of Lords.

SF: Were there any turning points or events that stand out during the campaign?

TD: Yes. The pandemic. Our ways of working and everything that we had planned to do suddenly shifted around. But I think, ultimately, it helped us for two reasons.

One, it provided us time. The Bill was suddenly going to take a lot longer. That allowed us time to counter the Government narrative, time to build our own narrative, and time to socialise the public with our counter narrative. We would have struggled to do that in the original timetable.

Second, the Government’s mistakes over the handling of the pandemic made the House of Lords irate, which gave it more impetus to rebel and defy the Government. The Bill was first introduced three months after the 2019 General Election, in which the Government had been returned with a resounding majority. In other circumstances, the House of Lords was highly unlikely to have stood in opposition to what they would have perceived to be a government with a very clear mandate.

SF: One of the most striking things about your campaign is that you succeeded in spite of that 80-seat majority in the House of Commons. Can you talk a bit about your public affairs approach?

TD: It was vital that, even though it didn’t matter in terms of the Parliamentary maths, which way Labour voted – , we still needed to win them over. As almost all Conservative MPs were standing up and giving their wholehearted support to the Bill, it was really helpful to have Labour MPs – as well as the Lib Dems and SNP – stand up and provide our narrative as that counterbalance.

That was incredibly helpful when it came to starting a coalition in the Lords.

SF: The narrative is a big part of the campaign, both yours and the Government’s. Can you talk a bit about how you approached messaging?

TD: As a joint campaign by Freedom from Torture and Survivors Speak OUT, all of the communications that went out came from survivor voices. All of our Parliamentary engagement was from a survivor perspective. I would say that this was a very persuasive argument for Labour..

At the beginning, Labour was buying the line ‘if you’re not with us, you’re against us.’ That was used against them, especially in the early debates. Conservatives were lining up to say, ‘oh, you don’t support our military’ and Labour wasn’t convinced they should oppose this. But a meeting with the Shadow Defence Ministers team seemed to be a turning point. Survivors asked, ‘How would you feel if a crime was committed against you 20 years ago and you couldn’t do anything?’

We also saw some of the UK’s most senior former military leaders coming out and opposing the Bill. We were able to time that just before Second Reading and that was a pivotal moment.

Over those 20 months, we shifted the narrative. The legislation began being referred to as the Torture Impunity Bill and the Government narrative of ‘you’re either with us or against us’ was being eroded.

The other aspect was unusual allies – for us – like the Royal Legion and the Centre for Military Justice coming out and saying that part two of the Bill negatively impacted British soldiers. Religious leaders spoke out, military leaders, academics, civil society. All that added to our hand.

Fortuitous timing came into play again because all of this shortly followed an investigation into Australian war crimes by Special Forces in Afghanistan. In Britain, we were able to point to the Australian report and say, ‘Look, they’re not trying to hide their war crimes!’

SF: Can you talk a bit about the challenges of ensuring staff welfare when you’re campaigning around something so immediate to them?

TD: That’s always on our mind. In the asylum advocacy work that we do it’s very personal. Your ability to have asylum is the first step of your safety, so we consciously address it in terms of staff wellbeing.

This was made more difficult by the pandemic and the fact that we were all dealing with the abrupt change and just the sheer horror of lockdown. I shudder thinking about it. But the pace of the campaign meant that we had to keep going – we couldn’t be overwhelmed by the pandemic.

That was very difficult. To be honest, our normal practices probably weren’t as effective because they’re so reliant on us seeing each other and reading each other’s body language. That sort of stuff doesn’t translate easily to Zoom. It took a bit of time for us to adjust and get a sense of the virtual realities. That was probably the hardest challenge we had. All those things we had in place just needed to be adapted on the go, whilst never really letting up with the campaign.

It was particularly difficult to keep up the momentum towards the end, when the Government announced it was going to remove crimes against humanity. It felt like it should be something to celebrate, but in reality the UK is really unlikely to ever actually pass that threshold. So, it’s not really a win. We had to stay in this one last dog fight to get war crimes removed. To re-engage straightaway. That was quite hard to manage.

But then of course we got the second win, with war crimes being removed and we really could celebrate. That was a great moment for us all.

Stop Torture Impunity won the SMK Campaign of the Year Award.