Aida Silvestri is a visual activist whose multi-faceted practice amplifies marginalised voices and migrant communities – raising awareness of human rights issues and representational politics in the arts and beyond. Read her full bio here.

Emma Boyd, Head of Marketing and Communications at SMK, and Aida met up to discuss the intersection between art and social change and to delve into Aida’s extraordinary contribution to change making and activism.

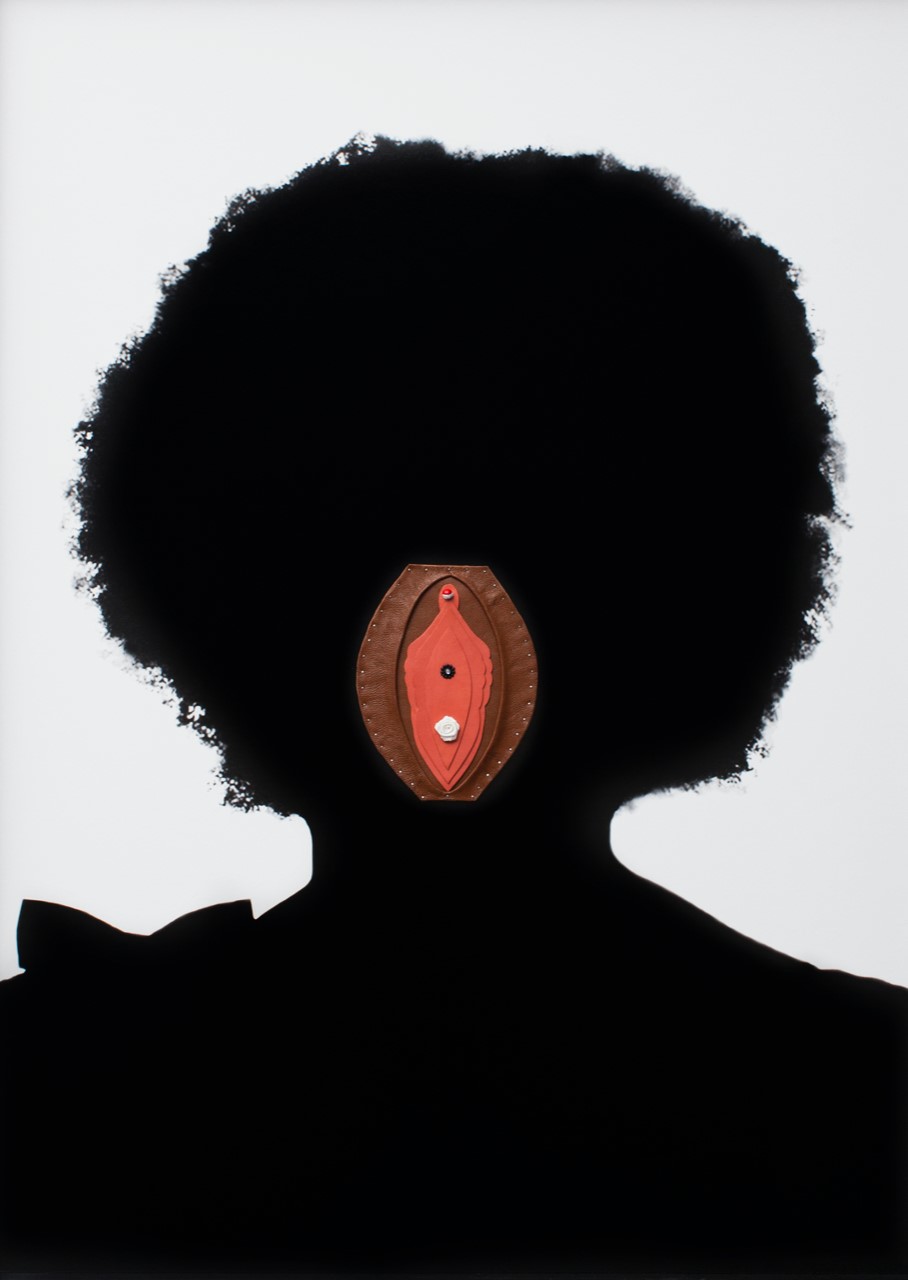

EB: I had the honour of seeing your exhibition Unsterile Clinic (2015) at Autograph ABP back in 2016. It was like nothing I had seen before in its approach to Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), a subject that is still considered so taboo. What really stood out for me were the small leather artworks that were also being used as visual aids for patients in specialist clinics within the NHS.

What has the impact of the work been and did you intend for it to have such a tangible outcome?

AS: The initial intent for producing Unsterile Clinic was mainly to learn about this unspoken practice, a practice that nearly ended my life and possibly the life of my first child during labour and was about to complicate my second pregnancy.

What started as self-awareness and self-healing became the necessity to expand and bring awareness to a broader audience. As an FGM survivor whose life wasn’t impacted by the procedure until pregnancy and labour, I wanted to learn more. Inspired by personal experience, I conducted an in-depth investigation into FGM. I attended focus groups where I met inspiring women living with the consequences of FGM daily. Further research led to the discovery that most FGM cases in the United Kingdom were diagnosed during pregnancy or labour. However, a few were not diagnosed until the second or third child after undergoing unexplained caesarean sections. These discoveries prompted me to create accessible visual aids explaining what was “normal” and what was mutilated.

I highlighted different types of cutting according to different tribes and cultures in the hope that some FGM victims don’t slip through the system and remain undiagnosed until it is an emergency, as I did. With my first pregnancy, nobody in the healthcare system knew what to do. By the time I had my second child, the NHS staff were aware and knew how to deal with someone in my condition. I feel I was part of the changes that have taken place regarding the awareness/ education of FGM.

Unsterile Clinic

TYPE I B

New commission. Courtesy © Aida Silvestri / Autograph ABP. 2016

EB: I love this quote from curator Renée Mussai about you: ‘Silvestri skilfully operates in the contested terrains where art and advocacy meet, photography and human rights converse, courageously and creatively addressing an urgent and critical condition affecting women and girls globally.’

You consider yourself a visual activist and use your art practice to raise awareness about pertinent socio-political issues. You also work as an educator, and volunteer in refugee camps, and with / in hospitals. Collaboration, as I understand, is central to your work so how does Aida the activist, Aida the artist and Aida the artist-educator come together?

AS: I always say that my work is activist, but I don’t feel that I am an activist because I don’t go out and protest and try to change legislation, and I dislike being in the public eye. I want my work to inform a possible change in the mindset of our broader population on socio-political issues and inspire people to take action.

First and foremost, my work is inspired by the community I am close to. In terms of process, I often start volunteering with an organisation or community outreach program. The artist educator in me may come out after volunteering for a while, and then the artist may come out. I always get to know the people I am working with; if something leads to artistic practice, fine. If it doesn’t, that is ok too. What I find satisfying is that some engagement work doesn’t lead to an outcome.

Over the years, I have taken hundreds of photographs of vulnerable people and asylum seekers in different stages of their claim. However, it doesn’t feel fitting to share those specific images because they were done for the purposes of gifting back and giving the individual a bit of power.

So, the volunteering Aida, the educator Aida and the artist Aida merge but sometimes the artist doesn’t have an outcome.

EB: What kind of volunteering work do you do?

AS: Over the years, I have volunteered/worked with different organisations, but currently, I am part of an organisation called Art Refuge, and I work with a team of artists and art therapists that supports the mental health and well-being of displaced people in Kent and Northern France through art and art therapy. We use ‘The Community Table’ to deliver projects. A large table adorned with maps and carefully selected innovative grounding materials provides an accessible and safe space to connect, collaborate, build, and play.

Our purpose is to be present, listen, and create a safe space for people to escape for a brief moment. There is healing that can take place, sometimes, there is a lot of play involved, and we produce excellent work collaboratively. It is beautiful that art can do that for people.

I also co-direct a small volunteer arts organisation called Origins Untold, which highlights work created by African diaspora people. We host cultural, creative, and social events to coincide with national and international celebrations of Black and African heritage in Kent.

EB: Your work challenges the status quo and deals with complex issues like prejudice and social injustice, highlighting politics of race, class, identity, and health.

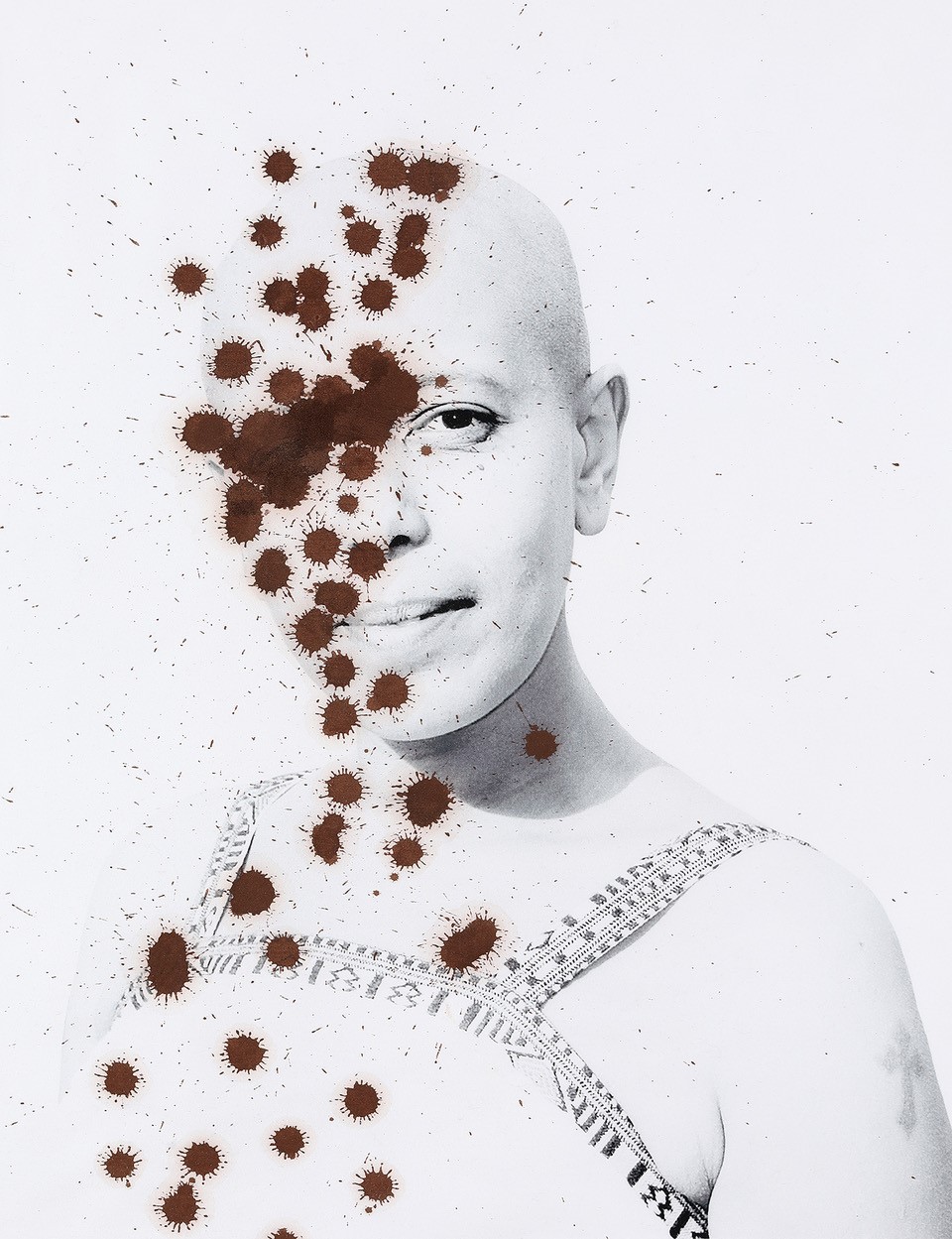

Do you think that art can truly bring about change to such systemic issues? I am also thinking of your recent body of work, Contagion: Colour on the Front Line made during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Contagion

Cacao

Commissioned by Autograph for Care I Contagion I Community – Self & Other (2020)

Courtesy of the artist / Autograph

AS: Socially engaged art can bring about change, but it needs to be in the limelight consistently for people to start engaging with these issues. If it is loud enough and people engage and listen, this is the route to change. Art is definitely a catalyst.

I want people to be informed by my work so they can go out and say, ‘Ok, this is happening, and I would like to do something about it.’ I want people to ask the right questions and be informed instead of making assumptions. Once informed, people can start to understand without prejudice or stereotyping interfering with their judgements.

Contagion was a commission from Autograph ABP as part of a larger commission of ten artists. During the pandemic, I was exposed to many headlines of people of colour dying. I remember a newspaper article with rows of dead brown faces on the front page simultaneously as Black Lives Matter protests were also taking place.

I began to question what was going on: we are getting killed by guns somewhere else, and there’s another thing, a virus that is disproportionately killing brown people. What is going on, and why is this happening? And there were other questions I started asking and connections I began to make about social, economic, and class issues that led me to think about commodities, slavery, and Empire. I began to draw connections between the enslaved people who worked in the plantations providing commodities to the Empire and many frontline workers who were risking their lives daily to provide commodities to those lucky enough to stay home and isolate.

The pandemic highlighted the deep-rooted inequality and injustice across all systems in the UK that lie dormant to the majority and are visible only as micro-aggressions to the minority on a daily basis and only grab the majority’s attention when an act of violence is committed, which motivates some to want to do more. We need to constantly confront injustice and not only as a result of a violent act, or when it is fashionable or trending. We cannot move forward as a society until we create a fair and equal system/world for everyone.

EB: As an activist whose work is rooted in socio-political issues, does your practice and approach to your work always have an end goal?

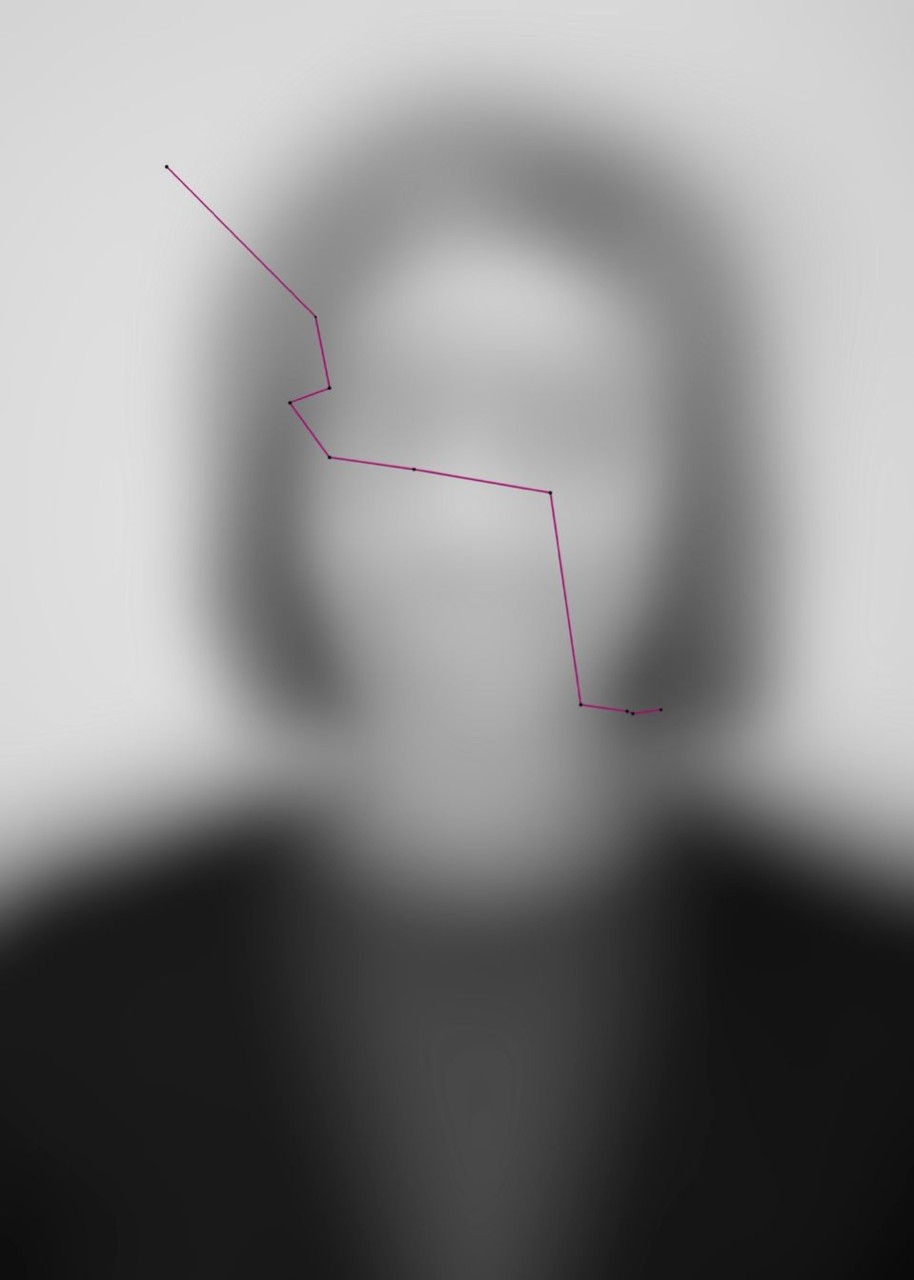

AS: No, it depends on the project and where it leads but my work always starts with the aim of raising awareness. For example, with Even This Will Pass (2013-2014), I wanted to do a project about Eritrea and the brutality that the government was accused of. During a period of research (2009-2012), I came across stories about many people dying in the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert. Yet, there was rarely any news about what was happening. There was some coverage in the Egyptian news but not much about this in the western news. We’re talking about 50, 30, 20 deaths, and nobody was reporting on this. I asked myself how many people have to die for this to become a headline.

What started as a political act became a humanitarian issue, and I wanted to tell those stories and experiences about people’s journeys so that people were prepared for what they were facing when considering crossing the Sahara Desert, the Mediterranean Sea, and the English channel. From speaking to many people in the UK, I realised everyone had done these kinds of journeys, so it was significant for me as a person of Eritrean heritage to highlight what was happening.

Even This Will Pass

KIDAN

Eritrea To London on foot, by car, boat, lorry, train and aeroplane. 2013

EB: When you are making the work, is there a target or specific audience you have in mind?

AS: This depends on the project. Sometimes my work is aimed at politicians or people in power, but ultimately, I want the wider population to learn from my art and take action in some way. Working with organisations that highlight similar issues of interest is paramount for disseminating important issues widely. I work closely with Autograph, Artrefuge, Counterpoints Arts and Imperial Health Charity and Origins Untold runs events around Black History Month, Windrush Day, and Refugee Week in Kent. By doing these events, we are trying to change the community’s mindset, promote integration and a sense of belonging. Working with schools is crucial, and we plan to do more of it, but a lack of funding limits what we can do, so this is always a challenge.

EB: What are the challenges of being an activist artist? Where does self-care come into the work you do?

AS: I cannot help that activism naturally finds itself in my work. I only engage with issues that are important to me. If this leads to no outcome, I don’t mind. The initial intention is always to create work because the work interests me. Some galleries and museums find my work challenging. I am thankful to those art institutions that advocate for my work and are willing to show it despite the risks.

I usually self-fund my projects and invest time because the project inspires me. Working with institutions with similar values is critical. I have to be very careful with my work because it can have consequences for people. Also, I work with many vulnerable people and therefore have to think sensitively about how to approach a project. I’m usually led and guided by the participants.

In terms of self-care, I have learnt a few grounding skills over the years. Also, working with a team of art therapists from Art Refuge weekly has expanded my understanding of self-care and self-preservation. It is so essential that I have the space to process. For example, after a session with Art Refuge, we might go to the seaside to debrief, process/discuss the session we just held, look at the waves, and connect with the sea. Furthermore, we have ‘The Community Table Collective’, which consists of fortnightly meetings, as another space for peer support, reflection, and self-care. These small practices help.

And something else I do is paint. I paint for myself. I find the process very relaxing and healing.

EB: The book Museum Activism investigates the changing role of museums, galleries and heritage organisations in activist practice, where there is explicit intent to act upon inequalities, injustices, and environmental crisis, that only a decade ago was met with scepticism and often derision.

These institutions that sought to purposefully bring about social change were viewed by many within and beyond the museum community as inappropriately political and antithetical to fundamental professional values. Today, the roles and responsibilities of museums as knowledge-based, social institutions is changing.

As an activist-artist, what is your experience of this shift and what do you think the role of museums and galleries should be in relation to social change?

AS: After the Black Lives Matter protests, there was a definite shift or surge in artists of the global majority working with museums, galleries, and art institutions on socio-political issues, but I still think it is a box-ticking exercise most of the time, and they must steer away from an ‘any artist of colour will do’ approach. There is something that institutions do when they have funding for a specific project with marginalised and vulnerable communities. They are fixated on what the outcome should be.

I often get approached by different organisations for a project with asylum seekers because they are aware of my involvement. I ask them questions like ‘have you done your research before designing the project’ and ‘have you spoken to people from that particular community?’ The answer I often get is, ‘this is why we approached you’. In most cases, my response to this work is ‘no, thank you’ because they didn’t approach me during the planning stage, or sometimes these projects do not benefit this community. I don’t like this kind of tokenism and I am still subject to it.

I carefully choose projects that genuinely engage with the community and invest in the research process. As an artist, I am trying to change this and want the engagement part to be the project’s main phase. Institutions need to be thinking of this most importantly. And there must be follow-up aftercare at the end of each project.

EB: The Chinese dissident artist Ai Wei Wei said ‘An artist must also be an activist – aesthetically, morally, or philosophically. That doesn’t mean they have to demonstrate in street protests, but rather deal with these issues through a so-called artistic language. Without that kind of consciousness – to be blind to human struggle – one cannot even be called an artist.’ I wonder how you feel about this statement and how you see yourself as a change-maker?

AS: Personally, I feel connected to Ai Weiwei’s statement. But I cannot impose activism into every artist’s work. I believe individual life experiences fuel and inspire activism. As a child, I experienced war, and these experiences inspired me and fueled my work to bring about change. I often say, ‘why do I always have to deal with all the difficult issues?’ and ‘why can’t I just do something that doesn’t take so much energy?’ I guess our lived experiences inspire our work.

EB: And finally, there are many inspirating artists working in change-based and issue-based arts practice today. Are there any that inspire you?

AS: I am inspired by mainly female and non-binary artists who engage with real tangible experiences and work that challenges the status quo.

Lola Flash‘s ‘Cross Colour Work’ is inspirational and ahead of its time. Laia Abril‘s works, especially ‘On Rape’ and ‘On Abortion‘ challenge gender-based stereotypes and religious myths. Monica Miranda‘s investigations on postcolonial politics of geography and history are very educational. We need more projects like Phoebe Boswell‘s work ‘The Space Between Things’, which deals with trauma and reflects on physical and emotional health. Zanele Muholi‘s work in confronting taboos and stereotypes faced by the black LGBTQI+ community in South Africa. And many more artists…

Ultimately, we should recognise works of many grass-root arts groups run by volunteers making tangible differences to promote communities whose contributions remain hidden or unrecognised.

EB: Thank you Aida! What a pleasure it has been to learn more about your art practice and activism.

At SMK, we are curious about how change happens and are interested in the intersection between art and social change. As part of our work to share our evolving understanding of social change, we will interview artists whose work is based in change-making and activism and who seek to understand and highlight contemporary social issues through their practice.